Software Designing: From Requirements to UI Flows

Software designing often fails for a surprisingly mundane reason: teams jump from a fuzzy idea to UI screens without doing the hard, clarifying work in between. The result is predictable, rework, scope creep, inconsistent UX, and engineering surprises that show up late (when they are most expensive).

This guide walks through a pragmatic, end-to-end software designing flow, from requirements to clear UI flows, with the artifacts and checks that keep product, design, and engineering aligned.

What “software designing” really includes (beyond UI)

In a modern product team, “design” is not just visual styling. It is the sequence of decisions that turns business goals into a system users can understand, operate, and trust.

Software designing typically spans:

- Problem framing (what outcome are we driving and for whom?)

- Requirements and constraints (functional, non-functional, policy, data)

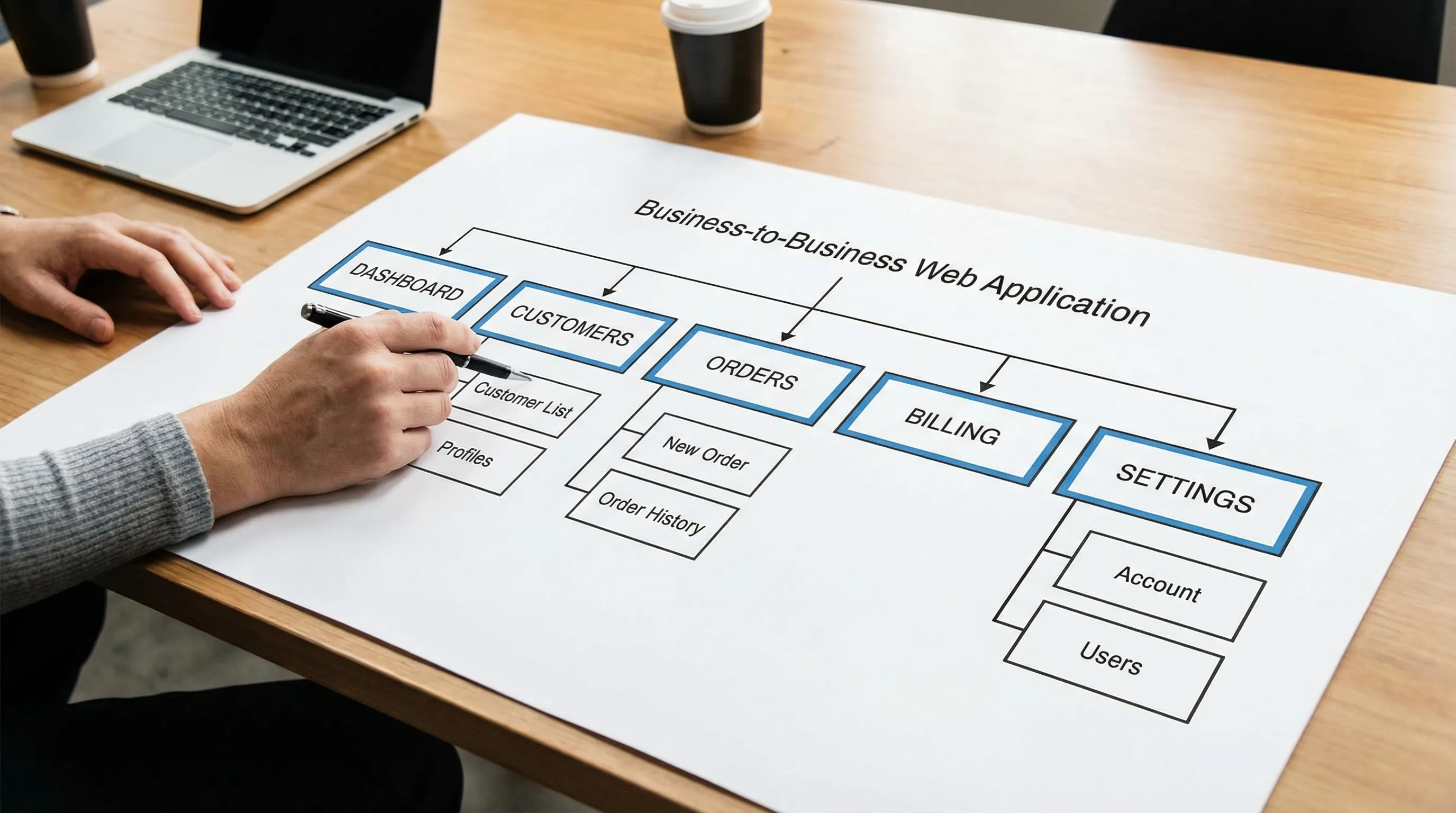

- Information architecture (how the product is structured)

- User journeys and UI flows (how people move through tasks)

- Interaction design (states, validations, errors, empty states)

- Accessibility and content (usable for everyone, clear language)

- Implementation alignment (hand-off details that prevent ambiguity)

If your team treats design as “make screens,” you end up specifying the surface while leaving critical behavior undefined.

Step 1: Start with outcome-focused requirements (not a feature wishlist)

Before you sketch a single screen, clarify what success means. Requirements work best when anchored to outcomes and constraints, not just requested features.

The minimum set of requirement inputs you want

Aim to capture these inputs early:

- Business outcome: revenue, conversion, retention, cost reduction, compliance, cycle time, NPS

- Primary users and contexts: roles, environments, device constraints, frequency

- Constraints: legal/compliance, branding, operational policies, platform limitations

- Non-functional requirements (NFRs): performance, availability, security, privacy, accessibility

- Data reality: source of truth, ownership, quality, latency, retention

If you need a more detailed requirements-to-delivery flow, Wolf-Tech’s companion guide on business software development from requirements to value is a good bridge between product thinking and engineering execution.

Use a “requirements spec” lightly, but intentionally

You do not need a 60-page document, but you do need shared clarity. IEEE’s requirements engineering standard (IEEE 29148) is a useful reference for what “good requirements” include (correct, unambiguous, verifiable), even if you apply it in a lightweight way.

A practical tactic: write requirements so they can be tested or observed.

- Ambiguous: “Fast checkout.”

- Verifiable: “Returning users can complete checkout in under 60 seconds on mobile (p95), excluding third-party payment confirmation.”

Step 2: Translate requirements into a domain model and key workflows

UI screens are a projection of your underlying domain. If the domain concepts are muddled, the UI will be too.

What to do (without heavy ceremony)

- Define the key nouns (entities): User, Account, Order, Invoice, Ticket, Property, Listing, etc.

- Define lifecycle states: Draft, Submitted, Approved, Rejected, Archived

- Define permissions: who can read, create, update, approve, export

- Map core workflows: create, search, update, approve, pay, cancel, audit

This step prevents a common failure mode: UI flows that “look right” but cannot be implemented cleanly because state transitions, ownership, or permissions were never decided.

| Design input | What you produce | Why it matters for UI flows |

|---|---|---|

| Outcome and user roles | Primary use cases per role | Prevents building flows for the wrong persona |

| Domain entities and states | State diagram or state table | Ensures screens cover real lifecycle transitions |

| Permissions and policy | RBAC notes, constraints | Avoids redesign when auth rules appear late |

| Data sources and integrity | Data ownership and validation rules | Drives form validation, error states, and messaging |

Step 3: Build information architecture (IA) before designing flows

Information architecture is the map of your product. UI flows are the routes people take through that map.

IA decisions you should make early:

- Navigation model: top nav, side nav, tabs, stepper, command palette

- Grouping and labels: what belongs together, what words users recognize

- Cross-links: where users naturally need shortcuts (for example, from Order to Customer)

- Search and filtering: the “escape hatch” for large datasets

A quick sanity check: if you cannot explain your IA in a 30-second product tour, your UI flows will likely be overcomplicated.

Step 4: Define UI flows as task stories with states (happy path plus reality)

A UI flow should describe how a user completes a task, including the decisions and system responses along the way. The biggest mistake is documenting only the happy path.

What a “good” UI flow includes

- Entry points: where the user starts (deep link, dashboard, search result)

- Steps and decisions: what the user does, what the system asks

- System states: loading, empty, partial data, stale data

- Validation: inline rules, server-side errors, permission blocks

- Recovery: undo, retry, drafts, save-and-resume, support escalation

- Exit points: what “done” looks like and where the user goes next

Nielsen Norman Group’s UX research is a helpful reference when you want evidence-based patterns for usability, error prevention, and user control (especially for enterprise UX).

A small example: “Change payment method” flow (condensed)

Instead of writing “screen 1, screen 2…”, phrase the flow as decisions and outcomes:

- User opens Billing.

- System shows current payment method and invoices.

- User chooses “Update payment method.”

- System requests re-authentication (policy constraint).

- User enters new details.

- System validates with payment provider.

- If validation fails, show reason and let the user retry or choose another method.

- If validation succeeds, confirm effective date and audit log entry.

Notice how policy (re-auth), integrations (provider validation), and operations (audit log) are part of the flow. That is software designing, not just UI.

Step 5: Turn flows into wireframes (focus on structure, not styling)

Wireframes are where ambiguity dies. Your goal is to make decisions visible:

- What information is on the page?

- What is the primary action?

- What is secondary?

- What does the user need to know to decide?

Two practical tips:

-

Design the empty state first for data-heavy screens. If the empty state is unclear, the whole feature will feel confusing.

-

Design the error state deliberately. Most “bad UX” is actually “bad error UX.”

Step 6: Add interaction rules that engineering can actually implement

A UI flow without interaction rules still leaves room for interpretation. This is where teams lose weeks.

Capture rules like:

- Field validation (format, ranges, required vs optional)

- Cross-field constraints (end date must be after start date)

- Autosave behavior (when, what triggers, conflict handling)

- Concurrency (what happens if the record changed elsewhere)

- Permissions messaging (hide vs disable vs show and explain)

A lightweight format that works well is a “state and rules table” attached to each flow.

| UI element / step | Rule | Example UX copy |

|---|---|---|

| Save button | Disabled until required fields valid | “Complete the required fields to continue.” |

| Submit action | Server validates business rules | “This order cannot be submitted because the customer is on hold.” |

| Edit form | Warn on unsaved changes | “You have unsaved changes. Discard or keep editing?” |

| Record view | Handle stale data | “This record was updated elsewhere. Refresh to see the latest version.” |

Step 7: Validate flows early with prototypes and “thin slices”

The fastest way to reduce waste is to validate before building.

You can validate at three levels:

- Concept validation: does the workflow match how users think?

- Usability validation: can users complete tasks without guidance?

- Feasibility validation: can you build a thin vertical slice through frontend, backend, and data?

That third point matters. A UI flow can be “usable” but still risky if it depends on messy data, missing integrations, or unclear security boundaries.

If you want a delivery-oriented view of de-risking, the build a web application step-by-step checklist complements this design-focused guide.

Step 8: Bake accessibility into flows (not as a final audit)

Accessibility is not just contrast and font size. It affects flows.

Examples of flow-level accessibility decisions:

- Can the flow be completed using only a keyboard?

- Do error messages help screen reader users understand what to fix?

- Are focus states and focus order predictable?

- Do modals trap focus correctly, and is there an accessible escape?

Using WCAG as a baseline helps teams translate “accessible” into testable criteria.

Step 9: Handoff: what engineering needs to build the UI flow correctly

A good handoff is not a pile of screens. It is a shared understanding of behavior.

Your handoff package should include:

- The UI flow (task narrative + decision points)

- Wireframes or high-fidelity screens with annotations

- Interaction rules (validation, states, edge cases)

- Analytics events (what you will measure and why)

- NFR notes that affect UX (performance targets, offline constraints, security prompts)

If you do this well, engineers will not need to “fill in the blanks” with guesses that later become product debates.

A practical UI flow checklist (use this in reviews)

Use this checklist when reviewing flows with product, design, engineering, and QA.

| Area | Questions to answer |

|---|---|

| Entry and exit | Where does the user start, and what does “done” look like? |

| Permissions | What happens if the user lacks access at each step? |

| Data states | Loading, empty, partial, stale, and error states defined? |

| Validation | What is validated client-side vs server-side, and what is the copy? |

| Recovery | Can the user undo, retry, save draft, or safely back out? |

| Accessibility | Keyboard, focus, screen reader announcements, and error clarity covered? |

| Measurement | What events or metrics confirm the flow is successful in production? |

Common failure modes (and how to avoid them)

“We have requirements” but they are not testable

If you cannot verify a requirement, you cannot design or build to it consistently. Convert vague statements into measurable acceptance criteria.

UI flows ignore operational reality

Approvals, audit logs, re-auth prompts, rate limits, and support escalation are not “edge cases” in real systems. Put them in the flow early.

Happy path only

Most user frustration happens in failure states: missing data, invalid input, conflicts, timeouts, permissions. Design for reality.

Design and engineering disagree on “what happens”

If behavior is not specified, the implementation becomes the spec. Annotate rules and states, then confirm them in a short cross-functional review.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between requirements and UI flows? Requirements define what the system must achieve (and constraints). UI flows describe how a user completes tasks within those constraints, including decisions and system states.

How detailed should a UI flow be? Detailed enough that a developer and QA engineer can implement and test it without guessing: entry points, decision points, states (loading, empty, error), validation rules, and recovery paths.

Should UI flows come before wireframes? Usually yes. Flows clarify the sequence and decisions, wireframes clarify layout and information hierarchy. They reinforce each other, but flows prevent designing disconnected screens.

How do we prevent rework between design and development? Define states and rules (validation, permissions, error handling), validate with a prototype, and align on a thin vertical slice that proves feasibility early.

Do UI flows matter for backend-heavy systems? Yes. Backend complexity shows up as user-facing constraints: permissions, data freshness, latency, and failure handling. Flows are where you make those constraints usable.

Need help turning requirements into buildable UI flows?

Wolf-Tech helps teams design and deliver custom software with a strong engineering foundation, especially when requirements are complex, legacy constraints exist, or quality and maintainability matter.

If you want a second opinion on your requirements, UI flows, or overall delivery approach, explore Wolf-Tech’s full-stack development and consulting services and reach out to discuss your project context.