Business Software Development: From Requirements to Value

Business software succeeds when it turns messy, real-world work into repeatable outcomes you can measure. Yet many teams still treat “requirements” as a document to complete, hand off, and forget. The predictable result is software that ships, but does not move the business.

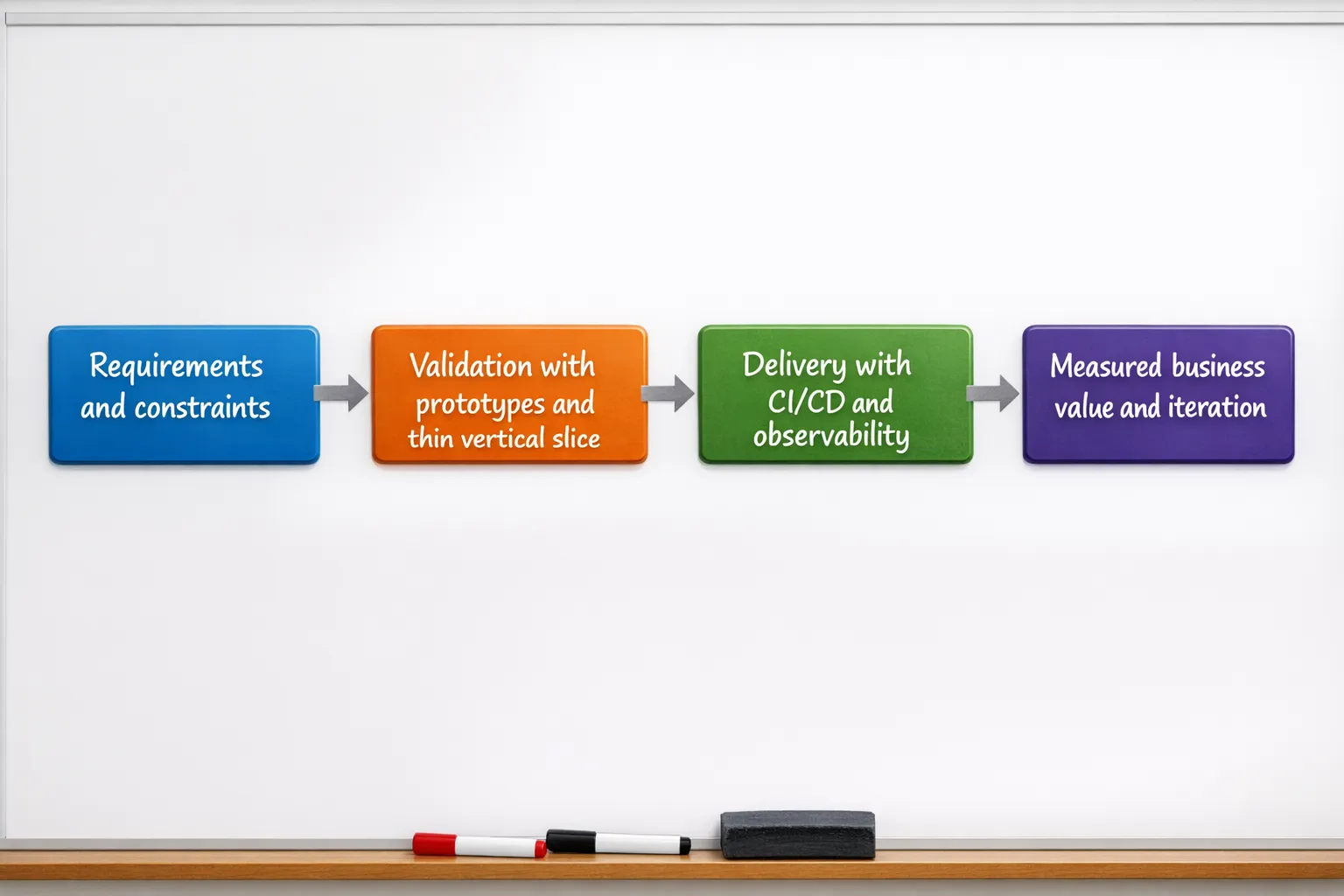

This guide breaks down business software development from requirements to value, showing how to define the right requirements, validate them early, deliver safely, and prove impact after launch.

Start with value, not features

A “requirement” is only useful if it helps you make a decision that increases business value or reduces business risk.

Before anyone writes user stories, align on four things:

1) The outcome you are trying to change

Write outcomes as measurable deltas, not aspirations.

Examples:

- Reduce order processing time from 2 days to same-day

- Increase quote-to-cash conversion from 18% to 25%

- Cut customer support tickets per 1,000 users by 30%

This becomes your value hypothesis. Requirements should exist to test and realize it.

2) The constraints you cannot violate

These are often more important than the feature list.

Common constraints:

- Compliance and data residency

- Availability and disaster recovery targets

- Integration realities (ERP, CRM, payment provider, identity)

- Delivery window (seasonal business, contract deadlines)

- Budget and team capacity

3) The users and stakeholders who define “done”

Business software typically has multiple “customers” inside and outside the company. If you only listen to the loudest stakeholder, you get political requirements, not operational clarity.

A practical approach is to map stakeholders by:

- Decision authority

- Workflow ownership

- Operational accountability (who gets paged, who handles escalations)

- Data stewardship (who owns quality, retention, and access)

4) What you will measure post-launch

If you cannot measure it, you cannot manage it.

Make measurement explicit early so the software is built with the necessary instrumentation (events, logs, audit trails, dashboards) from day one.

A good reference point for delivery performance metrics is the DORA research, which connects software delivery capabilities to organizational outcomes. DORA metrics are not business KPIs, but they help ensure you can deliver improvements frequently and safely.

Discovery: turn workflows into testable requirements

Most “requirements problems” are discovery problems. The team builds what was asked for, but what was asked for does not match how work actually happens.

Instead of starting with screens, start with the workflow.

Use workflow mapping to find the real requirements

Business software is usually a coordination engine across people, systems, and data. Mapping the workflow reveals:

- Where handoffs happen

- Where decisions are made (and by whom)

- Where information is missing or duplicated

- Where exceptions dominate the happy path

A simple workflow map often exposes that the “requirement” is not “add a new dashboard,” it is “reduce rework caused by missing data at step 3.”

Triangulate what people say with what systems show

Interviews are necessary, but they are not sufficient. Add system evidence:

- Support ticket themes

- CRM notes

- ERP or inventory adjustments

- Audit logs

- Cycle time data from existing tools

This is how you prevent building software around folklore.

Example: requirements in a service business

If you run a field service operation, requirements often hide inside scheduling and exception handling. A residential services company like Sun City Garage Door might care less about “a new admin portal” and more about outcomes like faster dispatch, fewer missed appointments, and tighter coordination between estimates, parts, and technician availability. Those are value statements that lead to better requirements.

Specify requirements so engineering can deliver safely

Great requirements reduce ambiguity without becoming a bureaucratic novel. The goal is shared understanding: what must happen, what must never happen, and how you will know.

A helpful mental model is to separate:

- Functional requirements (what the system does)

- Non-functional requirements (how well it must do it)

- Data and integration requirements (what it must connect to and what it must store)

- Operational requirements (how it runs, is monitored, and is supported)

Functional requirements: define behavior and edges

Functional requirements are most useful when they include:

- Trigger and expected outcome

- Primary flow

- Top exceptions (the 20% that cause 80% of the pain)

- Acceptance criteria written in observable terms

For business software, exception handling is rarely “edge.” It is the product.

Non-functional requirements: translate “it needs to be fast” into numbers

Non-functional requirements (NFRs) are where many projects derail because they are implied rather than explicit.

Make them measurable:

- Performance: p95 latency under X ms for key workflows

- Availability: 99.9% for customer-facing flows, different for internal tools

- Security: SSO, MFA, audit logging, least privilege

- Privacy: retention windows, deletion rules

- Operability: alerting, runbooks, on-call expectations

A widely used standard for requirements engineering is ISO/IEC/IEEE 29148, which provides guidance on what “good requirements” look like (correct, unambiguous, verifiable). You can start with a simplified version and only add rigor where the risk demands it.

Data and integration requirements: name the sources of truth

Business software usually fails at the seams between systems.

Clarify early:

- System of record for each entity (customer, invoice, product, appointment)

- Data ownership and stewardship n- Sync model (real-time API, batch, event-driven)

- Identity model (how users and permissions map across systems)

If you do not define sources of truth, you will accidentally create competing truths.

A requirements-to-risk table you can reuse

Use this as a lightweight way to ensure each requirement has a validation method and a risk signal.

| Requirement area | What to capture | How to validate early | What to measure in production |

|---|---|---|---|

| Workflow behavior | Primary flow plus top exceptions | Clickable prototype, walkthrough with real cases | Cycle time, drop-off rate, exception rate |

| Performance | p95 targets for key operations | Load test on a thin slice | p95 latency, saturation, error rate |

| Security | Authn/authz, audit needs, threat assumptions | Threat modeling session, security review | Auth failures, privilege escalations, audit completeness |

| Integrations | APIs, data contracts, error handling | Contract tests, sandbox integration spike | Integration error rate, retries, queue lag |

| Data quality | Validation rules, deduping, reconciliation | Backfill test on sample data | Reconciliation drift, manual corrections |

Validate requirements before you scale delivery

The highest ROI moment in software development is catching the wrong direction early.

Validation does not mean a 10-week discovery that produces a 60-page spec. It means proving the risky assumptions with the cheapest credible test.

Prefer a “thin vertical slice” over a big design phase

A thin vertical slice is a minimal, end-to-end implementation of one meaningful workflow across UI, API, and database, including basic operability.

Why it works:

- It surfaces integration and data issues early

- It forces clarity on NFRs (performance, auth, audit)

- It produces a working baseline you can iterate on

If you want a practical build checklist for this phase, Wolf-Tech has a companion guide: Build a Web Application: Step-by-Step Checklist.

Use prototypes to validate usability and workflow alignment

For internal business tools, usability issues often show up as:

- Workarounds in spreadsheets

- “Shadow IT” tools

- Inconsistent data entry

A prototype walkthrough with real scenarios can eliminate weeks of rework.

Spike solutions when uncertainty is technical, not product

If your main unknown is technical feasibility (for example, integrating a legacy ERP, or meeting latency targets), run a time-boxed spike to reduce uncertainty, then update estimates and scope based on evidence.

Convert requirements into a delivery plan that protects value

Once requirements are validated, the next failure mode is execution that burns time without compounding value.

Prioritize by value and risk, not loudness

A simple prioritization lens:

- Highest value, highest risk: do early (prove and de-risk)

- Highest value, low risk: schedule for predictable delivery

- Low value, high risk: challenge hard, often cut

This prevents the common trap of delivering easy features first while postponing the hard, value-critical work.

Make architecture a business decision

Architecture is not about trends, it is about operational outcomes.

Pick an architectural baseline based on:

- Required change speed (how often you expect change)

- Integration surface area

- Reliability needs

- Team size and skills

If you are actively selecting or modernizing your stack, this guide can help structure the decision: How to Choose the Right Tech Stack in 2025.

Define “done” beyond feature completion

For business software, “done” should include:

- Monitoring and alerting for key failure modes

- Audit trails where needed

- Documentation for runbooks and support

- Data migration and reconciliation steps

- Rollback plan for risky releases

This is how requirements translate into value reliably, not just theoretically.

Prove value after launch (this is where most teams stop too early)

Shipping is the midpoint. Value arrives when the workflow changes in the real world.

Instrument the product to answer “did it work?”

Tie your original outcomes to measurable signals:

- Adoption: active users in the target role, task completion frequency

- Efficiency: time to complete workflow, rework rate, handoff delays

- Quality: error rates, support tickets, data correction volume

- Revenue: conversion, upsell, churn, AR aging

If value depends on human behavior change, measure that behavior directly.

Connect product analytics to operational analytics

Business software must be operable. Combine:

- Product events (user actions)

- System metrics (latency, errors)

- Business KPIs (conversion, cycle time)

This helps you distinguish “users are confused” from “the system is slow” from “the process itself is broken.”

Run post-launch reviews that result in backlog changes

A practical cadence:

- Week 1: stability and urgent fixes

- Week 2 to 4: adoption and workflow friction

- Week 4+: KPI movement and iteration

If you never revisit requirements after launch, you are treating them as a contract instead of a hypothesis.

Common pitfalls (and how to avoid them)

Treating requirements as a one-time phase

Reality changes. Your understanding improves. Requirements must be revisited as evidence comes in.

Over-indexing on features instead of workflow outcomes

Feature lists are easy to approve and hard to defend. Outcomes force prioritization.

Ignoring non-functional requirements until production

Security, performance, and operability are expensive to retrofit. Make them explicit early and validate them with the thin slice.

Not budgeting for change management

Business software changes behavior. Training, rollout planning, documentation, and stakeholder alignment are part of delivery.

Where Wolf-Tech fits

If you are building or modernizing business-critical software and want a path from requirements to measurable outcomes, Wolf-Tech can support across:

- Full-stack development for custom digital solutions

- Tech stack strategy and architecture guidance

- Cloud and DevOps foundations for reliable delivery

- Code quality consulting and legacy code optimization when existing systems constrain progress

For budgeting discussions, this can help you frame scope and ROI trade-offs: Custom Software Development: Cost, Timeline, ROI.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is business software development? Business software development is the process of designing, building, and operating software that supports or differentiates business workflows, such as order management, scheduling, billing, compliance, internal operations, and customer portals.

How detailed should requirements be for custom software? Requirements should be detailed enough to be unambiguous and testable (especially around exceptions and non-functional needs), but not so detailed that they lock in a solution prematurely. Aim for clarity on outcomes, workflows, constraints, and acceptance criteria.

What is the difference between requirements and acceptance criteria? Requirements describe what the system must do and under what constraints. Acceptance criteria define the observable conditions that must be true for a requirement to be considered complete and correct.

How do we avoid building the wrong thing? Validate early with prototypes and a thin vertical slice, prioritize by value and risk, and instrument the product so you can confirm whether real workflows improved after launch.

Which metrics matter most after launch? Use a mix of business KPIs (cycle time, conversion, revenue, cost to serve) and software delivery and reliability metrics (lead time, deployment frequency, error rate, p95 latency). The right set depends on the outcome you defined upfront.

When should we modernize legacy systems versus build new? Modernize when the legacy system still contains valuable domain logic or data and you can replace it incrementally. Build new when constraints, architecture, or cost make incremental change impractical. Often the best approach is hybrid (modernize and extend while gradually replacing the most limiting parts).

Turn requirements into measurable outcomes

If your next initiative is stuck in vague requirements, competing stakeholder demands, or unclear ROI, Wolf-Tech can help you shape a practical path from discovery to delivery, with the engineering rigor needed to make value measurable.

Explore Wolf-Tech’s approach to custom builds, optimization, and technical strategy at Wolf-Tech.