Custom Software Applications: Build vs Buy vs Hybrid

Choosing between building, buying, or blending software is rarely a pure “tech” decision. It is a business decision with engineering consequences: speed to value, risk exposure, operating cost, and how differentiated your product can become.

If you are evaluating custom software applications in 2026, the most expensive mistake is usually not “building when you should have bought” or “buying when you should have built.” It is choosing without an explicit model for fit, integration reality, and long-term ownership.

This guide gives you a practical way to decide build vs buy vs hybrid, plus concrete hybrid patterns that reduce lock-in and keep delivery moving.

Build vs buy vs hybrid (what each really means)

Most teams talk about build vs buy as if there are only two options. In practice, hybrid is the default for modern application portfolios.

Buy (off-the-shelf)

You adopt a SaaS product or packaged platform and configure it. “Buying” still includes work: data migration, integrations, access control, reporting, training, and often paid add-ons.

Typical examples: CRM, HRIS, accounting, ticketing, e-signature, CMS, analytics tools.

Build (custom)

You create a bespoke application that matches your workflows, domain model, and constraints. You own the code and the pace of change, but you also own operational responsibility.

Typical examples: customer portals, marketplaces, internal operations tooling for unique processes, regulated workflows requiring auditable behavior.

Hybrid

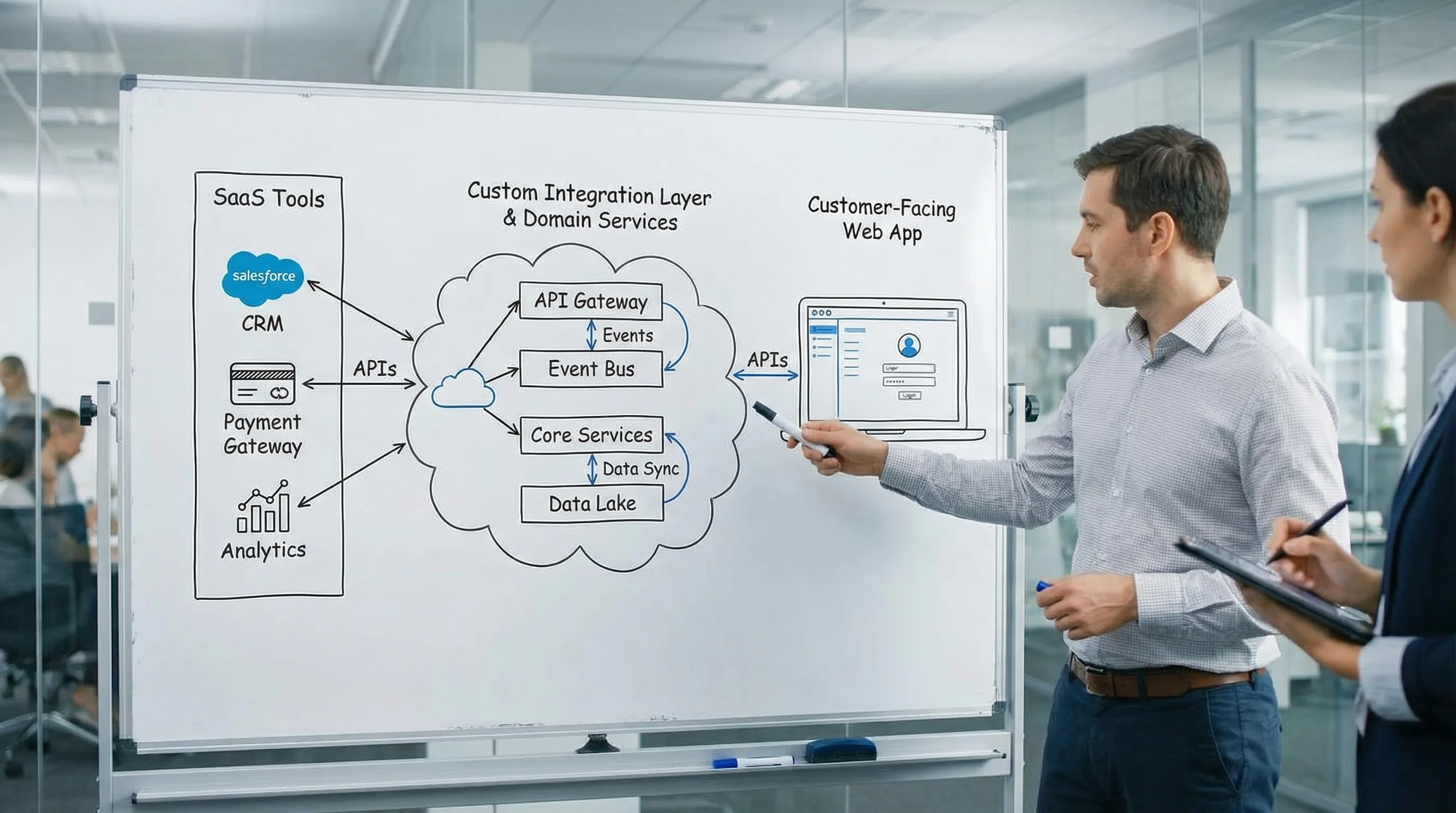

You combine bought components with custom code, typically by:

- Buying a system of record (or multiple systems) and building an integration layer

- Building differentiating experiences on top of a platform (custom UI, custom rules engine, custom workflows)

- Wrapping legacy systems while incrementally modernizing them

Hybrid is not a compromise. Done well, it is a deliberate architecture and ownership strategy.

A decision framework that works for real teams

A good build/buy decision is evidence-based, not preference-based. Start with these six questions, and force specific answers.

1) Is this capability a differentiator or a commodity?

If the capability is truly differentiating (it drives retention, conversion, margin, risk reduction, or a proprietary workflow), building often makes sense.

If the capability is commodity (email marketing, basic invoicing, generic HR workflows), buying usually wins.

The trap: calling everything “differentiating” because it touches revenue. Differentiation is about whether your approach must be meaningfully unique.

2) How much misfit can you tolerate?

Bought software always has a mismatch with your process. The question is whether the mismatch is acceptable.

Ask:

- Can we change our process without breaking compliance, customer experience, or unit economics?

- Are we comfortable with the product’s workflow, permissions model, and reporting model?

If you are in a domain where “the process is the product” (for example underwriting flows, complex pricing, regulated approvals), misfit can be a deal-breaker.

3) What is the integration reality (not the PowerPoint)?

Most cost and risk hides in integration. The core question is not “does it have an API?” It is:

- Can we build reliable, observable integrations with acceptable latency and failure modes?

- Can we reconcile identities, permissions, and tenant boundaries?

- Can we keep data consistent across systems without manual firefighting?

If integrations are deep and business-critical, hybrid patterns become central.

4) What constraints are non-negotiable?

Common hard constraints:

- Data residency and privacy requirements

- Auditability and traceability

- Security and supply-chain requirements

- Uptime and recovery targets (RTO/RPO)

Buying can still work in regulated environments, but you must be able to verify controls. Referencing recognized frameworks can help anchor due diligence, for example NIST SSDF for secure development expectations and OWASP ASVS for application security verification.

5) What is your time-to-value window?

If you need value in weeks, buying or hybrid (buy core, build edge) typically beats building from scratch.

But be careful: “buy is faster” is only true when configuration + integration + migration stays bounded. Many implementations slip because the organization discovers hidden workflow complexity late.

6) Who will own this in 12 to 24 months?

Ownership is where many decisions fail.

- If you build: do you have (or can you realistically hire) the team to run it, evolve it, and keep it secure?

- If you buy: do you have someone responsible for vendor management, renewal leverage, and keeping the configuration sane?

- If hybrid: who owns the seams (integration, data contracts, identity, observability)?

A practical scorecard

You can run a lightweight scoring exercise in a workshop. Keep it simple, score each dimension from 1 (favors buy) to 5 (favors build).

| Dimension | 1 (Favors buy) | 3 (Depends) | 5 (Favors build) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differentiation | Commodity process | Some unique rules | Core differentiator |

| Workflow fit | Standard workflows OK | Moderate customization | Unique workflow required |

| Integration depth | Few integrations | Several integrations | Many critical, real-time integrations |

| Compliance and auditability | Standard vendor controls OK | Some gaps to mitigate | Must prove custom controls |

| Change velocity | Quarterly changes OK | Monthly changes | Weekly or daily change needed |

| Data ownership and portability | Low risk | Needs planning | High lock-in risk |

Use the score to drive discussion, not to “auto-decide.” The point is to surface where risk and cost will land.

When buying off-the-shelf is the right call

Buying is usually optimal when the capability is well understood in the market, your requirements are not unique, and the main risk is execution speed.

Strong signals to buy

- You need fast time-to-value and can adopt standard workflows

- Your differentiators are elsewhere (for example, your customer experience layer, pricing model, or data product)

- The product has proven ecosystem support (integrations, SSO options, export paths)

- You can negotiate contracts that protect you (data portability, security evidence, exit terms)

Hidden costs buyers underestimate

- Integration build and long-term maintenance

- Data migration and reconciliation, including “last 10 percent” edge cases

- Identity and authorization mapping (roles rarely align cleanly)

- Operational overhead (monitoring integrations, handling failures)

- Custom reporting and analytics needs (often outside the tool’s sweet spot)

If you are buying, treat implementation as an engineering project with production-grade standards, not as “just configuration.”

When building custom software applications is the right call

Building makes sense when software is how you win, or when off-the-shelf constraints would force you into risky workarounds.

Strong signals to build

- The workflow is a differentiator and changes frequently

- You need an opinionated domain model (not just fields and forms)

- You have complex authorization, multi-tenant logic, or audit requirements

- You must integrate deeply with multiple systems and cannot accept brittle sync jobs

- Vendor options create unacceptable lock-in or cost scaling

What you must be ready to do well

Custom does not only mean “write code.” It means creating a delivery and operating capability.

At minimum, treat these as non-negotiable:

- Measurable non-functional requirements (latency, availability, recovery, security)

- A reliable delivery system (CI/CD, quality gates, progressive releases)

- Observability and operational readiness (logs, metrics, tracing, runbooks)

If you want a deeper end-to-end view of what “good” looks like, Wolf-Tech has a detailed companion guide on the lifecycle: Custom Software Application Development: End-to-End Guide.

Hybrid: the approach most organizations should default to

Hybrid is how you avoid two extremes:

- Buying a platform and then forcing it to behave like your custom product

- Building everything yourself and reinventing commodity capabilities

The key is to be explicit about boundaries: what you buy, what you own, and what contracts connect them.

Common hybrid patterns (and when to use them)

| Hybrid pattern | What you buy | What you build | Best for | Key risk to manage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buy core, build differentiators | System of record (CRM, ERP, CMS) | Custom UX, rules, workflows | When your advantage is experience or logic | Vendor API limits, version drift |

| Integration layer (API facade) | Multiple SaaS tools | A stable internal API + adapters | When you need to change vendors without rewrites | Data consistency, observability |

| Strangler around legacy | Legacy stays in place | New services/screens incrementally | Modernization without disruption | Dual-write complexity, migration sequencing |

| Extension model | Platform with plugins/webhooks | Plugins, automations, custom modules | When platform extensibility is strong | Plugin sprawl, upgrade breaks |

| Data hub / event stream | SaaS operational tools | Warehouse + governed pipelines | Cross-tool reporting and AI readiness | Data governance, lineage |

A strong hybrid design tries to ensure that your custom code depends on your own stable contracts, not on every vendor detail.

The “integration tax” is real, budget it intentionally

If you choose hybrid, accept that integration is product work:

- Define data contracts (what is authoritative where)

- Decide sync strategy (events, CDC, batch), and failure behavior

- Instrument integrations like production services

In modern stacks, hybrid often benefits from an architecture review early. If you want a structured view of what an expert should examine, see: What a Tech Expert Reviews in Your Architecture.

Total cost of ownership (TCO): model it beyond year one

Year-one cost is a poor decision metric. You need a TCO view because the cost curves differ:

- Buy often has lower initial delivery cost, but can grow with seats, usage, add-ons, and implementation complexity.

- Build has higher initial cost, but can reduce per-unit costs and unlock faster iteration if you invest in engineering fundamentals.

Use a category-based model instead of trying to guess a single “total.”

| Cost category | Buy | Build | Hybrid |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upfront delivery | Lower (often) | Higher | Medium |

| Integration and data migration | Often underestimated | Needed, but under your control | Highest, needs discipline |

| Ongoing change cost | Depends on vendor flexibility | Under your control | Split across vendor + custom |

| Security and compliance evidence | Vendor-provided plus your due diligence | Your responsibility | Shared responsibility, needs clarity |

| Exit and portability | Contract-dependent | Typically easier (you own code) | Must be designed (contracts, abstractions) |

If you need a more detailed way to estimate costs, timelines, and ROI for custom initiatives, this guide is useful context: Custom Software Development: Cost, Timeline, ROI.

Risk controls that make any option safer

The best decisions include safeguards that keep you from getting trapped.

For buying

Focus on verifiable evidence and exit paths:

- Data export formats and frequency (including historical data)

- Security posture evidence (SOC 2 reports where applicable, vulnerability management, incident handling)

- SLA definitions that match business risk (including support response)

- Clear contract clauses for termination, data deletion, and transition support

For building

De-risk by proving delivery capability early:

- Ship a thin vertical slice to production (even if behind a flag)

- Establish CI/CD and quality gates from day one

- Define operational ownership (on-call expectations, runbooks, incident process)

For hybrid

Make seams explicit:

- Create canonical definitions for identities, roles, and permissions

- Standardize integration patterns (retries, idempotency, timeouts)

- Treat vendor dependencies as versioned adapters, not hardwired calls

A pragmatic 30-day plan to decide (without analysis paralysis)

You can usually reach a defensible decision in a month if you timebox the right work.

Week 1: Align on outcomes and constraints

Document:

- Business outcome and success metrics

- Non-negotiable constraints (compliance, residency, latency, availability)

- Systems involved and the data you must own

Week 2: Market scan plus fit checks

Shortlist realistic vendor options and run scripted demos around your hardest workflows. Avoid “happy path” demos.

Week 3: Integration spike

Do a small technical proof:

- Authenticate (SSO if needed)

- Read/write the critical objects

- Validate rate limits, webhooks, eventing, and failure modes

Week 4: TCO and risk review

Finalize:

- Scorecard results and decision rationale

- A phased roadmap (what to buy now, what to build, what to postpone)

- An exit strategy (even if you never use it)

If you want a broader build-vs-buy lens and additional decision signals, you can also compare with: When to Choose Custom Solutions Over Off-the-Shelf.

Where Wolf-Tech fits

Wolf-Tech helps teams make and execute these decisions with an engineering-first approach, especially when the answer is “hybrid” and the complexity sits in architecture, legacy constraints, and delivery reliability.

Depending on what you need, that can include:

- Full-stack implementation of custom applications

- Architecture and code quality consulting (to de-risk build decisions)

- Legacy code optimization and modernization (to enable hybrid migration paths)

- Cloud, DevOps, database, and API work to make integrations reliable at scale

If you are at the decision point now, a focused discovery or architecture review is often the fastest way to replace assumptions with evidence and commit to a plan you can actually deliver.