Next JS React: App Router Patterns for Real Products

Most teams can ship a working Next.js demo in a week. Shipping a maintainable Next JS React product that supports authentication, permissions, complex navigation, safe mutations, and predictable performance is where most App Router implementations start to wobble.

This guide focuses on practical App Router patterns for real products: how to structure routes, draw server/client boundaries, choose between Server Actions and Route Handlers, design caching and revalidation, and build UX flows (modals, tabs, dashboards) without turning your codebase into a maze.

The App Router mental model (the part that affects architecture)

The App Router is not “Pages Router with different folders”. It is a different set of defaults that matter in production:

- Server Components by default: your safest, fastest default for product pages that read data.

- Explicit client boundary (

"use client"): every time you cross it, you pay in bundle size and hydration. - Layouts are composition units: they are not just for nav bars, they are where you define data and UI boundaries for whole product areas.

- Loading and streaming are first-class:

loading.tsxand Suspense-friendly components change how you build responsive UIs. - Caching is a feature: Next.js can cache server

fetchcalls, and you can explicitly revalidate via tags and paths.

If you align on these defaults early, the “right” patterns become much easier to enforce across a growing team.

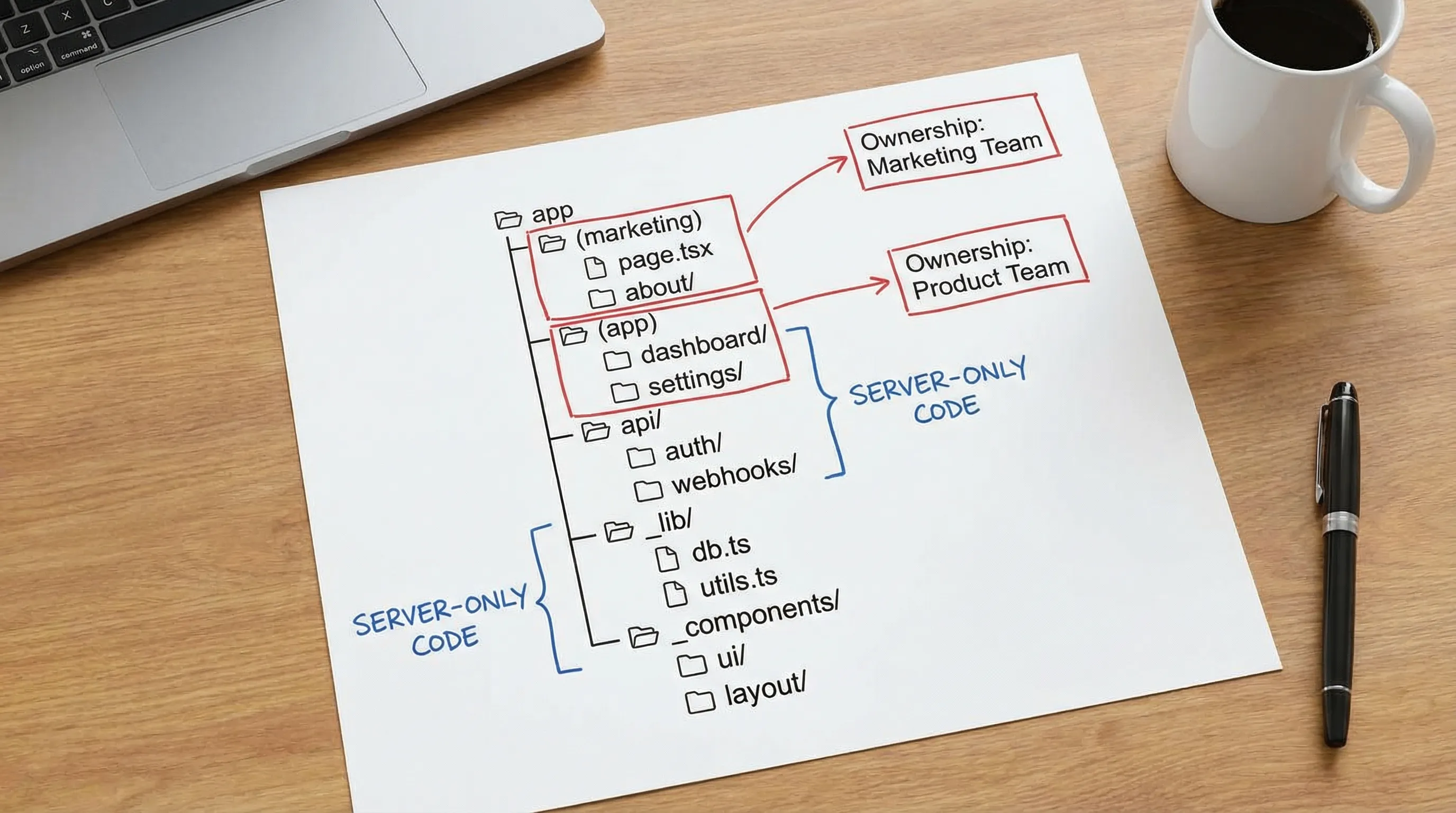

Pattern 1: Route groups that mirror the product, not the URL

A common failure mode is organizing the app/ folder like a framework tutorial, then struggling when the product grows.

For real products, route groups are your friend because they let you map areas of the product (marketing, app, docs, admin) without changing the URL structure.

A pragmatic baseline:

app/

(marketing)/

page.tsx

pricing/page.tsx

layout.tsx

(app)/

layout.tsx

dashboard/page.tsx

settings/

layout.tsx

profile/page.tsx

billing/page.tsx

api/

webhooks/route.ts

_components/

_lib/

Why this works:

- You can enforce different performance and security defaults per area (for example, marketing can be highly cached, app pages typically less so).

- You reduce “global layout” complexity. Marketing and authenticated app experiences rarely belong in one layout.

- You gain clean seams for ownership when multiple teams work in the same codebase.

A small naming rule that prevents chaos

Pick a convention and stick to it:

app/(group)/feature/page.tsxfor routingapp/_componentsfor cross-app UI building blocksapp/_libfor server-only utilities (DB, API clients, auth helpers)

If you prefer feature-first organization, you can still do it, but keep routing entrypoints obvious. Teams lose time when they cannot answer “where is the route for this screen?” in 10 seconds.

| Structure choice | Works best when | Watch out for |

|---|---|---|

Route-first (app/.../page.tsx is the center) | Small to mid apps, clear navigation tree | Shared business logic can scatter unless you add _lib/modules |

| Feature-first (domain modules own most logic, routes are thin) | Multi-team products, complex domain logic | Higher initial discipline required, or routes become hard to trace |

Pattern 2: Treat server and client as a contract boundary

A reliable heuristic for Next JS React apps:

- Server Components: data access, permissions, assembling page payloads, secure transformations.

- Client Components: interactivity, optimistic UI, complex local state, browser-only APIs.

What tends to go wrong is pushing everything client-side “because React”, then reintroducing a homemade BFF layer, losing performance and security.

A production-friendly pattern is:

- A route

page.tsx(Server Component) loads the minimum data needed. - It renders a client component that receives a typed, validated payload.

// app/(app)/dashboard/page.tsx

import { getDashboardData } from "@/app/_lib/dashboard";

import DashboardClient from "./DashboardClient";

export default async function DashboardPage() {

const data = await getDashboardData();

return <DashboardClient initialData={data} />;

}

This is not about purity, it is about keeping the sensitive, expensive, and cacheable parts on the server by default.

Pattern 3: One read model per route, explicit caching per route

In real products, “data fetching” becomes a reliability problem: stale dashboards, inconsistent numbers, surprise cache misses, and slow pages.

Start with an explicit per-route decision:

- Is this page allowed to be stale (marketing, docs, public listings)?

- Must it be fresh (billing, permissions, admin actions)?

- Is it a mix (dashboard shell can be cached, but widgets refresh frequently)?

Next.js provides multiple levers (rendering strategy, fetch caching, revalidation), but the operational pattern is the key: document the route’s data contract.

A simple decision table that teams can actually follow:

| Route type | Example | Default approach | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public, content-like | landing page, docs | Cache aggressively | Great fit for static generation or revalidation |

| Public, data-like | marketplace listings | Cache with revalidation | Prefer stable pagination and query defaults |

| Authenticated, user-specific | dashboard | Server render, selective caching | Beware cross-user caching, validate auth server-side |

| Highly sensitive | billing, admin, security settings | No caching, strict auth | Prefer server-only data access and explicit audit logging |

If your team needs a deeper walkthrough of caching, ISR, and performance trade-offs, pair this article with Wolf-Tech’s guide on Next.js performance tuning.

Pattern 4: Mutations, pick Server Actions or Route Handlers on purpose

In App Router products, mutations usually fall into three buckets:

- Form submissions (create/update simple entities)

- Complex workflows (multi-step operations, background jobs)

- Integrations (webhooks, third-party callbacks)

App Router gives you two main primitives: Server Actions and Route Handlers. Both can be valid, but mixing them randomly leads to inconsistent validation, auth, and observability.

A pragmatic rule

- Use Server Actions for product UI forms where you want tight coupling to the component tree and progressive enhancement.

- Use Route Handlers for API-like concerns: webhooks, callbacks, mobile clients, queue ingestion, or when you need explicit HTTP semantics.

| Choice | Best for | Strengths | Risks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Server Actions | UI-driven mutations | Co-located with UI, fewer network hops in your mental model | Can become a dumping ground for business logic if you do not enforce service boundaries |

Route Handlers (app/api/.../route.ts) | Webhooks, external API calls, cross-client APIs | Clear HTTP boundary, easier to secure with conventional patterns | Teams sometimes rebuild a full REST API “by accident” without governance |

Production tip: enforce idempotency for anything that charges money or triggers side effects

Payments, emails, provisioning, and background jobs should be designed to tolerate retries (from users, browsers, proxies, and your own systems). Make idempotency a default requirement, not an afterthought.

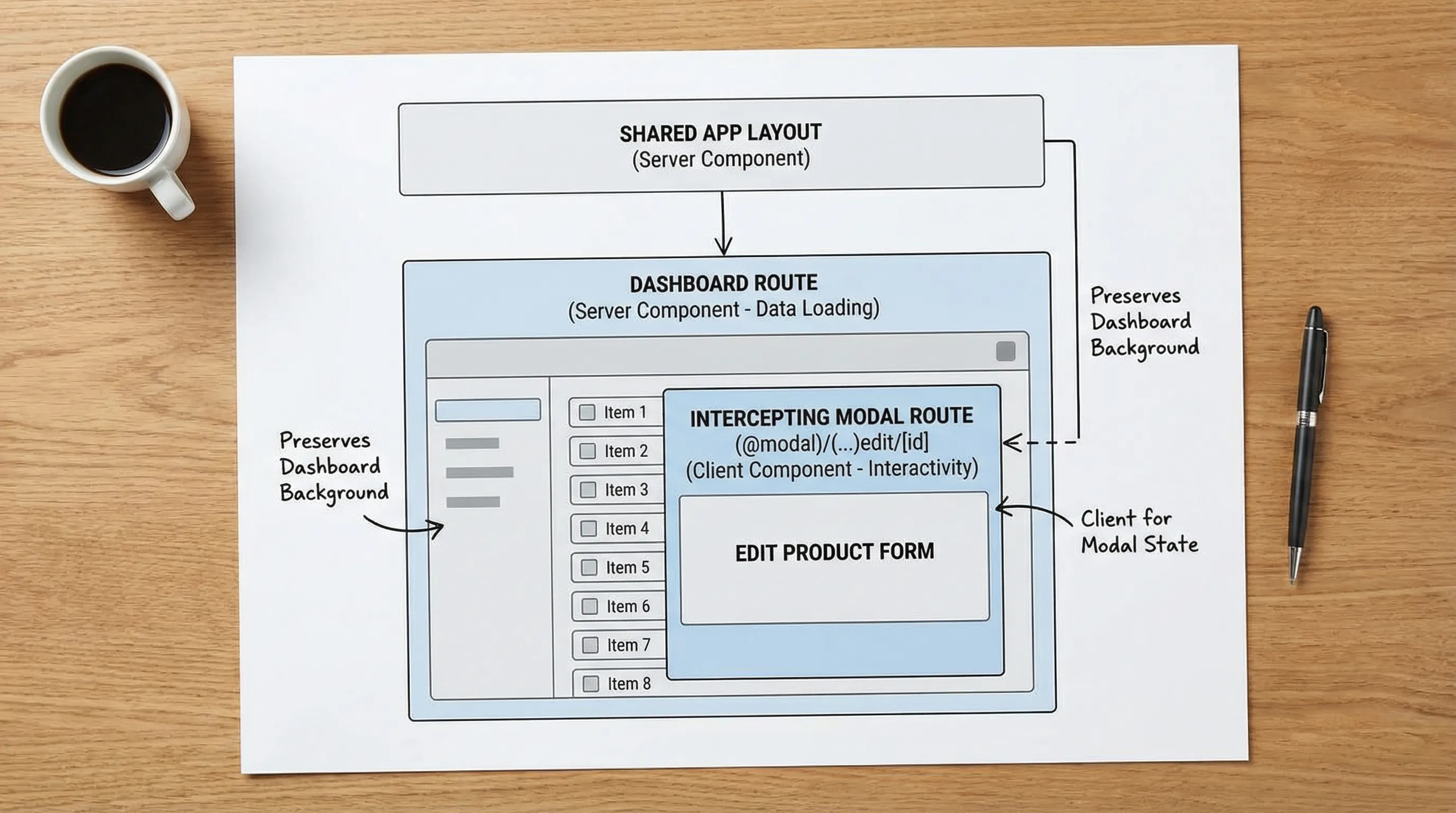

Pattern 5: Complex navigation with parallel routes and intercepting routes

Real products often need:

- Modal flows that preserve the page context (edit item, invite member)

- Tabbed settings where each tab is addressable

- Split-pane dashboards

This is where App Router shines, but only if you use the routing patterns intentionally.

A common, scalable approach:

- Use parallel routes for areas that can render independently (for example, a list and a details panel).

- Use intercepting routes for modals that should be deep-linkable while keeping the underlying page.

This avoids “stateful modal spaghetti” and makes navigation shareable and testable.

If your UI layer is getting complex, it can also help to standardize core React patterns. Wolf-Tech’s React patterns for enterprise UIs is a good companion for component architecture and state boundaries.

Pattern 6: Loading, errors, and “real world resilience” boundaries

A production app is not defined by the happy path, it is defined by how it behaves under partial failure.

App Router gives you dedicated files that you should treat as product requirements:

loading.tsx: define skeletons that match your layout, not generic spinners.error.tsx: a user-friendly failure mode, plus a place to log exceptions.not-found.tsx: distinguish “missing resource” from “error”.

Two practical rules:

-

Put

error.tsxboundaries around product areas, not just globally. A failing widget should not take down the whole app shell. -

Design empty states and partial-data states. Dashboards especially should remain useful when one card fails.

This is also an observability win: scoped errors provide better signals than a single “everything failed” boundary.

Pattern 7: Auth and authorization that survives refactors

Most Next JS React security bugs come from blurred responsibility. UI hides a button, but the server still allows the action.

A durable pattern is:

- Authentication and tenant resolution happen server-side first.

- Authorization is enforced close to the data.

- Client components are allowed to enhance UX, but never to decide access.

Middleware is for routing decisions, not for full authorization

Middleware can be useful for:

- Redirecting unauthenticated users away from app routes

- Normalizing tenant context (subdomain, path-based)

- Setting headers for downstream behavior

But avoid putting heavy business authorization in middleware, because you want authorization to be consistent across pages, actions, and background processes.

Visible authorization in the UI

Even though the server must enforce permissions, it still helps to make authorization visible and testable in the UI. For example, a Can component that consumes a server-provided permissions payload can standardize how the UI adapts to roles.

For broader security-by-design practices (threat modeling, SDLC controls), the OWASP Top 10 remains a useful baseline.

Pattern 8: Multi-tenant products, treat caching as a security feature

Multi-tenancy is where teams accidentally leak data, especially when caching is involved.

Common tenant models:

- Subdomain (

tenant.example.com) - Path prefix (

example.com/t/tenant/...) - Header-based (rare for browser apps, more common internally)

Whichever you use, establish these rules:

- Tenant resolution is explicit (a function that resolves tenant ID from host/path and validates it).

- Every data access includes tenant scope (queries, API calls, storage keys).

- Caching and revalidation are tenant-aware.

If you cannot confidently answer “could this response ever be cached and served to the wrong tenant?”, you should treat the route as dynamic and disable caching until you can.

Pattern 9: File uploads and background work, do not block user requests

Real products upload files, run imports, generate reports, and process webhooks.

A robust approach in Next.js:

- The UI triggers a mutation that enqueues work (or requests a signed upload URL).

- A background worker does the heavy lifting.

- The UI polls or subscribes for status updates.

This avoids timeouts and reduces error rates, especially under load.

If you are modernizing an existing system to support these flows incrementally (without breaking business operations), Wolf-Tech’s guide on modernizing legacy systems without disruption aligns well with this “thin slice + reversible releases” approach.

Pattern 10: A “product-grade” App Router checklist you can adopt

Treat this as a set of review prompts for PRs and architecture decisions:

- Does this route have a clear server/client boundary, or did we push data access into the client?

- Is the caching policy explicit for this route (fresh vs stale, and why)?

- Are mutations using the right primitive (Server Action vs Route Handler), with consistent validation and auth?

- Are loading and error states defined at the product-area boundary?

- Are tenant, auth, and permissions enforced server-side?

- Can we observe failures (logs, traces, error reporting) without reproducing locally?

If you want a broader scalability view beyond App Router specifics, Wolf-Tech’s Next.js best practices for scalable apps expands into architecture and delivery considerations.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is App Router ready for large Next JS React products? Yes, many teams ship large products with App Router successfully. The key is adopting consistent patterns for server/client boundaries, routing structure, caching, and mutations, instead of mixing approaches per feature.

Should we use Server Actions everywhere? Not usually. Server Actions are great for UI-driven mutations (especially forms), but Route Handlers are often a better fit for webhooks, third-party callbacks, and API-like endpoints that need explicit HTTP semantics.

How should we organize routes for marketing pages and the authenticated app? Use route groups like (marketing) and (app) with separate layouts. This keeps concerns separated, avoids bloated global layouts, and lets you apply different caching and security defaults.

How do we prevent cross-tenant caching issues in multi-tenant apps? Make tenant resolution explicit and ensure all data access is tenant-scoped. Treat caching as potentially security-sensitive, and keep routes dynamic until tenant-aware caching and revalidation are clearly implemented.

What is the most common App Router mistake in production? Overusing client components. When too much logic and data fetching moves into the client, bundle size grows, auth gets inconsistent, caching becomes unpredictable, and performance tuning becomes harder.

Need an App Router architecture review before it gets expensive?

If your Next.js codebase is growing and you want confidence in your App Router patterns, Wolf-Tech can help with full-stack development, legacy code optimization, and code quality consulting.

Get in touch via Wolf-Tech to discuss an architecture review, a migration plan from legacy routing, or hands-on implementation support.