Web Application: What Is It and How Does It Work?

A “web application” is one of those terms everyone uses, but teams often mean different things by it. For a product leader it can mean “our customer portal.” For engineering it can mean “a browser-based client plus APIs plus data.” For a CFO it can mean “a system we can roll out without app-store friction.”

This guide defines what a web application is, then walks through how it works end to end, from the moment a user clicks a link to the moment data is read, validated, and returned.

What is a web application?

A web application (web app) is software that users access through a web browser and that typically:

- Responds dynamically to user input (not just reading content)

- Uses server-side logic (business rules) and usually persistent data storage

- Manages identity and permissions (logins, roles, entitlements)

- Integrates with other systems (payments, CRM/ERP, analytics, third-party APIs)

A helpful way to frame it is: a web app is a product experience delivered over the web, where the browser is the user interface, and the “application” is split across client and server.

Web application vs website (quick comparison)

A static marketing website can be “web-based,” but it is not always an “application” in the product sense.

| Dimension | Website (typical) | Web application (typical) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary goal | Inform, persuade | Let users complete tasks and workflows |

| Personalization | Limited | Common (accounts, roles, data per user) |

| Data writes | Rare | Frequent (create/update/delete) |

| Business logic | Minimal | Central, enforced on the server |

| Integrations | Few | Common (payments, identity, internal systems) |

| Change risk | Lower | Higher, needs testing, monitoring, rollback |

If you are building dashboards, portals, internal tools, marketplaces, booking flows, onboarding funnels, claims processing, or anything with permissions and data, you are in web application territory.

How does a web application work? (From click to data and back)

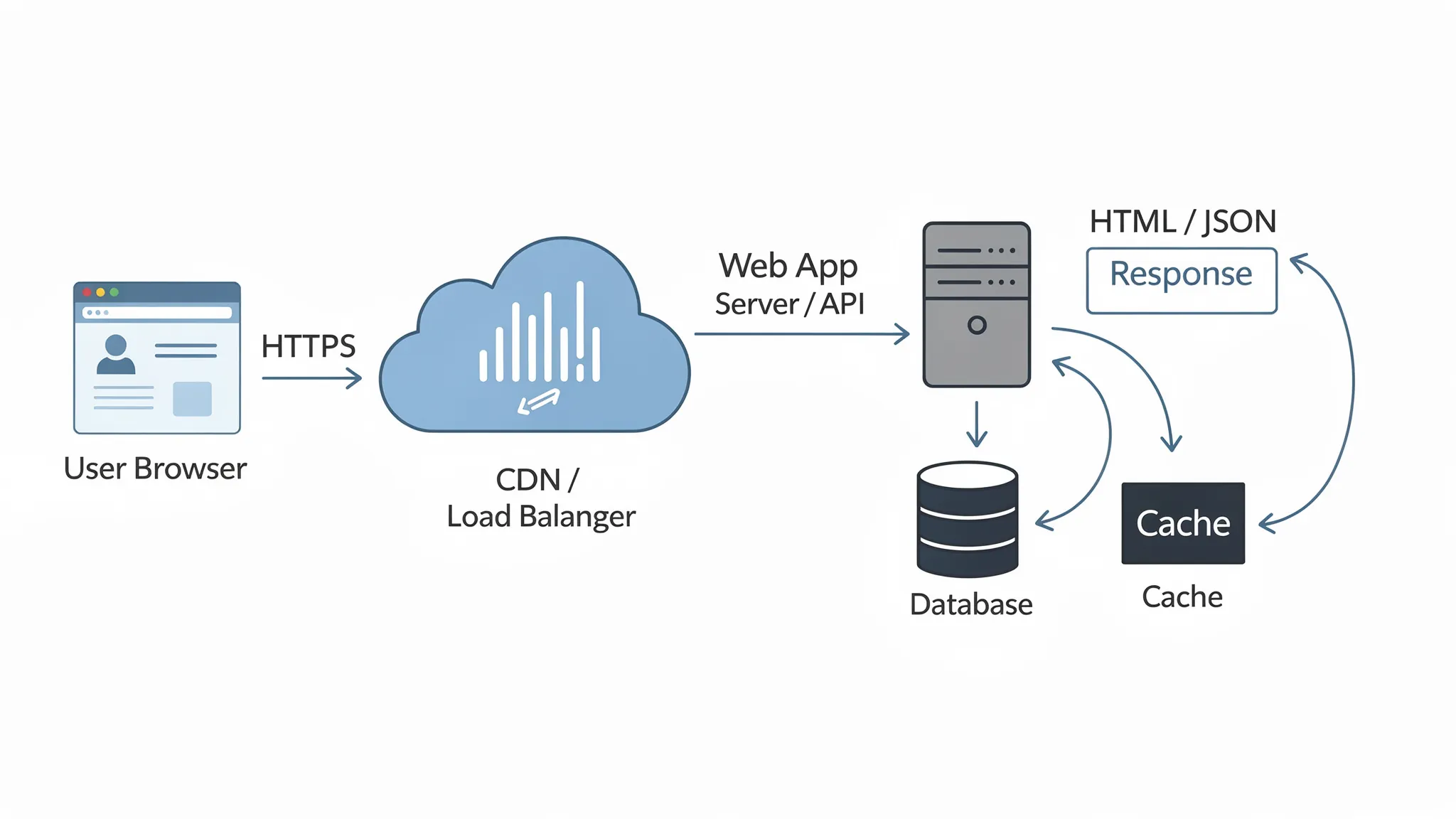

At runtime, most web apps follow the same fundamental loop: request, compute, data access, response, render, interact.

1) The browser finds your app (DNS) and opens a secure connection (TLS)

When a user navigates to yourapp.com, the browser:

- Resolves the domain to an IP address via DNS

- Opens a connection (usually HTTPS) and negotiates encryption via TLS

This is foundational because everything else (authentication, API calls, payments) depends on transport security. If you want a reliable overview of HTTP and how the web exchanges messages, MDN is a solid reference: MDN Web Docs: HTTP.

2) The request hits the “edge” (CDN) or a load balancer

In modern setups, a request often goes through:

- A CDN (content delivery network) for caching static assets (JS, CSS, images) and sometimes dynamic pages

- A load balancer that distributes traffic across multiple application instances

- A WAF (web application firewall) in front of your app in higher-risk environments

This layer is mostly about performance, resilience, and basic security filtering.

3) The application server runs business logic

Once the request reaches your application runtime (for example Node.js, Java, .NET, Python, Go), the server typically:

- Routes the request to the correct handler (page route, API endpoint)

- Validates input (schemas, types, required fields)

- Enforces authentication and authorization (who are you, what are you allowed to do)

- Applies business rules (pricing, eligibility, workflow state transitions)

- Calls internal services or third-party APIs

This is where “web app” becomes meaningfully different from “web page.” The server is not just returning content, it is executing domain rules.

4) Data is read and written (database, cache, queues)

Most web apps rely on a data layer composed of:

- Primary database (relational or NoSQL) for system-of-record data

- Cache (often key-value) for speed and reduced database load

- Message queue / event bus for background processing and integrations (emails, invoicing, data sync)

Even simple “CRUD” apps can become complex here, because correctness and performance are tightly coupled to data modeling, indexing, and transaction boundaries.

5) The server sends a response (HTML or JSON)

Depending on the architecture, the response could be:

- HTML (server-rendered pages)

- JSON (API responses consumed by client-side code)

- Redirects, cookies, and caching headers

At this point, your edge caching strategy matters. Cache too aggressively and users see stale or unauthorized data. Cache too little and costs and latency climb.

6) The browser renders UI and runs JavaScript

Once the browser receives HTML/CSS/JS:

- It parses and renders the page

- It executes JavaScript that attaches event handlers and fetches additional data

- In many modern stacks, it “hydrates” server-rendered markup so the UI becomes interactive

This is also where user-perceived performance is won or lost. Measuring with user-centric metrics is key. Google’s Core Web Vitals are a common starting point for shared performance targets.

7) Ongoing interaction: API calls, real-time updates, and navigation

After initial load, web apps keep working through:

- API calls on user actions (submit form, update record)

- Client-side navigation (common in SPAs)

- Real-time updates (WebSockets, Server-Sent Events) where needed

- Background jobs (exports, notifications, reconciliation)

From a business perspective, this is where web apps deliver leverage: workflows, automation, and data visibility that improve outcomes.

The core components of a web application (and what each is responsible for)

Teams often talk about “the web app” as if it were one thing, but it is more accurate to think in components with clear responsibilities.

| Component | What it does | What to get right |

|---|---|---|

| Browser UI (frontend) | Rendering, input handling, client-side state | UX/accessibility, bundle size, error handling |

| Web server / app runtime | Routing, business logic, auth enforcement | Maintainability, testability, safe deploys |

| API layer | Contract between clients and services | Versioning, validation, authorization, rate limiting |

| Data stores | Persist and query data | Modeling, indexing, migrations, backups |

| Identity (authN/authZ) | Login and permissions | Least privilege, session/token safety |

| Infrastructure | Hosting, networking, scaling | Cost control, resilience, IaC, environment parity |

| Observability | Logs, metrics, traces, alerting | SLOs, fast diagnosis, low-noise alerts |

If you want your web app to scale beyond the first release, treat these as first-class engineering concerns, not afterthoughts.

Common types of web applications (and how their “how it works” differs)

A lot of confusion comes from mixing “web application” with a specific rendering model. Here are the common types you will hear in 2026.

| Type | How it works (in practice) | When it’s a good fit |

|---|---|---|

| MPA (multi-page app) | Each navigation loads a new page from the server | Content-heavy apps, simpler interactivity, predictable SEO |

| SPA (single-page app) | Initial load fetches a JS app, navigation is client-side, data via APIs | Highly interactive UIs, app-like dashboards |

| SSR (server-side rendering) | Server renders HTML per request, browser hydrates for interactivity | Performance-sensitive pages, SEO needs, fast first render |

| SSG / ISR (static generation / incremental regeneration) | Pages prebuilt (and sometimes refreshed) to reduce runtime work | Marketing + docs + mixed apps, speed at scale |

| PWA (progressive web app) | Adds offline-ish capabilities and installability via service workers | Field apps, intermittent connectivity scenarios |

A single product can combine these patterns. The goal is not to “pick the trend,” it is to pick the behavior that matches your risk profile (SEO, speed, complexity, team maturity).

What makes web applications hard (and what to plan for)

The “hello world” of web apps is easy. The operational reality is where teams get surprised.

Security is not optional

Web applications are exposed by design, and attackers automate discovery and exploitation. At minimum, align your build and review practices with known categories like the OWASP Top 10.

The recurring pitfalls we see across teams:

- Authentication and session mistakes (token leakage, weak rotation, missing re-auth for sensitive actions)

- Broken access control (users can access data they should not)

- Injection and XSS risks (especially with rushed validation)

- Supply-chain exposure (dependencies, build pipeline integrity)

Security is most cost-effective when built into architecture, CI, and code review norms, not bolted on at the end.

Performance is a product feature

A web app is a distributed system: browser, network, edge, app server, database, third-party scripts. Slowness can come from any layer.

Two practical takeaways:

- Measure separately: frontend experience (Core Web Vitals) and backend latency (p95/p99)

- Avoid “optimizing” before you instrument, guessing is expensive

If you are building with Next.js specifically, Wolf-Tech has deeper performance guidance in the blog, for example: Next.js Development: Performance Tuning Guide.

Reliability and operability decide long-term cost

A web app that cannot be debugged quickly becomes expensive, regardless of how fast it shipped.

Reliability usually comes down to basics done consistently: timeouts, retries with care, idempotency, safe deploys, and good observability. If reliability is a priority for your domain, see: Backend Development Best Practices for Reliability.

Maintainability is a strategic constraint

Your first version is rarely your last. Architecture that supports change wins.

For many teams, that means:

- Clear module boundaries

- Tests that lock behavior (especially around money and permissions)

- Gradual evolution instead of big rewrites

Wolf-Tech’s modernization content goes deep on this topic, for example: Code Modernization Techniques: Revitalizing Legacy Systems.

Do you need a web application? A fast decision filter

If you are unsure whether you are building a “site” or a “web app,” ask these questions:

- Will users log in and see different data based on identity or role?

- Are there workflows with state (approval, onboarding, fulfillment, claims, audits)?

- Do users create or change data that must be validated and retained?

- Do you need integrations (payments, CRM, ERP, data warehouse, identity provider)?

- Does success depend on speed, reliability, or compliance (not just aesthetics)?

If you answered “yes” to two or more, treat the project as web application engineering, not just web design.

What to do next if you’re planning a web app

Once you’ve decided “yes, this is a web app,” the next step is reducing risk early. The highest-leverage early work is usually:

- Clarify outcomes and constraints (who, what, how success is measured)

- Validate the critical path with a thin slice (one end-to-end workflow)

- Choose an architecture and stack that matches your stage and team

- Set non-functional requirements (security, performance, reliability) as explicit targets

For practical implementation guidance, you can use Wolf-Tech’s step-by-step resources:

- Web Apps Development: A Practical Starter Guide

- Build a Web Application: Step-by-Step Checklist

- How to Choose the Right Tech Stack in 2025

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a web application in simple terms? A web application is software you use in a browser to complete tasks, not just read information. It runs business logic on a server and usually stores and processes user data.

How does a web application work step by step? Typically: your browser resolves the domain (DNS), opens a secure HTTPS connection (TLS), sends an HTTP request to the app, the server runs business logic and talks to data stores, then returns HTML or JSON that the browser renders and makes interactive.

Is a web application the same as a website? Not usually. Websites are often content-first and mostly read-only. Web applications are interactive, personalized, and centered on workflows, data writes, permissions, and integrations.

Do web applications always need a backend? Most do, because business rules, security enforcement, and persistent data generally belong on the server. Some “frontend-only” apps exist, but they often still rely on third-party APIs for identity and storage.

What’s the difference between a SPA and a web application? A SPA (single-page application) is a frontend rendering/navigation pattern. A web application is the overall product system (frontend plus backend, data, identity, infrastructure). Many web apps are SPAs, but not all.

Are web applications secure by default? No. You need intentional security design and ongoing practices (secure authentication, correct authorization, input validation, dependency management, and secure CI/CD).

How do I choose the right architecture for a web app? Start from outcomes and constraints (traffic, SEO, compliance, team size), then validate with a thin vertical slice. Avoid premature complexity like microservices unless you have clear drivers.

Build (or improve) your web application with Wolf-Tech

If you’re planning a new web application, modernizing an existing one, or struggling with performance, reliability, or legacy constraints, Wolf-Tech can help with full-stack development, code quality consulting, legacy optimization, and tech stack strategy.

Explore the capabilities at Wolf-Tech and use the guides above to align your team before you start building.